|

CRASTER WAR MEMORIALS World War Two About the Project |

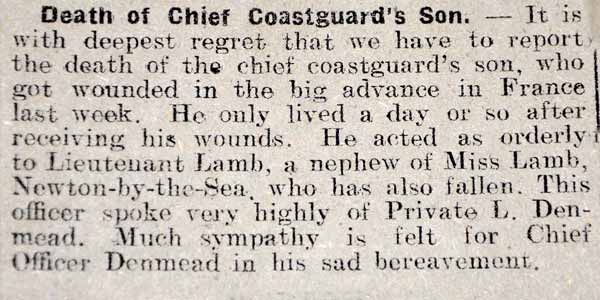

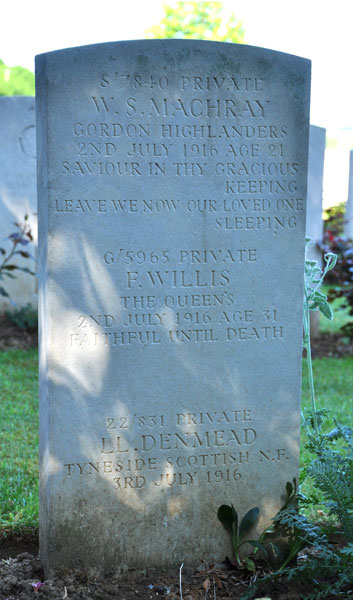

Llewellyn DenmeadPrivate Llewellyn Denmead of the Northumberland Fusiliers 22nd (Tyneside Scottish) Bn. Service No. 22/831 died of his wounds at the 36th Casualty Clearing Station, located in Helley on the Somme, on July 3rd 1916, aged 20. Llewellyn is buried at Heilly Station Cemetery, 10km south west of Albert. Llewellyn was the son of William Llewellyn and Sarah Denmead. His father was chief coastguard in Craster during the war and they lived in the top house in the row of Coastguard cottages on Whin Hill. Theirs was a large family and one that moved around, as the 1901 census return tells us, as William's job as a coastguard took him around the country. Their eldest son William was born in 1890 in Weston Super Mare, the next four children, Elizabeth (1891), Ernest (1892) Edgar (1893) and Florence (1895) were born in Burnmouth. Llewellyn (1896) was born in Newton by Sea and Arthur (1898) and Frederick (1900) were born in (here the census return is illegible, but it looks like) Hauxley, Northumberland. The family cannot be found in the 1911 census, although Edgar had returned to Burnmouth where he was working as a 'boyservant'. The Commonwealth War Grave citation for Llewellyn gives a Weston Super Mare address for his father William. Llewellyn's brother Arthur died of pneumonia in 1918 and brothers Frederick, Edgar and Ernest fought in the war and are listed on St Peter's Roll of Honour. The following article appeared in the Alnwick and County Gazette on July 15th 1916:

He was awarded the British War and Victory medals. The following account of Casualty Clearing Stations can be found at http://www.1914-1918.net/ccs.htm "The Casualty Clearing Station was part of the casualty evacuation chain, further back from the front line than the Aid Posts and Field Ambulances. It was manned by troops of the Royal Army Medical Corps, with attached Royal Engineers and men of the Army Service Corps. The job of the CCS was to treat a man sufficiently for his return to duty or, in most cases, to enable him to be evacuated to a Base Hospital. It was not a place for a long-term stay. CCS's were generally located on or near railway lines, to facilitate movement of casualties from the battlefield and on to the hospitals. Although they were quite large, CCS's moved quite frequently, especially in the wake of the great German attacks in the spring of 1918 and the victorious Allied advance in the summer and autumn of that year. Many CCS moved into Belgium and Germany with the army of occupation in 1919 too. The locations of wartime CCSs can often be identified today from the cluster of military cemeteries that surrounded them." The following is taken from a much longer, very moving, diary written by a volunteer surgeon at a CCS at http://www.firstworldwar.com/diaries/casualtyclearingstation.htm "The institution of these small mobile hospitals near the fighting line had revolutionized the surgery of the War, and was the means of saving thousands of lives. It was found that the fatal sepsis and gas gangrene of wounds could be avoided if effective operation was performed within thirty-six hours of their infliction, and all dead and injured tissue removed, in spite of the extensive mutilation incurred. The essential parts of a C.C.S. were: (1) A large reception marquee. (2) A resuscitation tent, where severely shocked or apparently dying cases were warmed up in heated beds, or transfused before operation. (3) A pre-operation tent, where stretcher cases were prepared for operation. (4) A large operating tent with complete equipment for six tables. (5) An evacuation tent, where the cases were sent after operation, to await the hospital train for the Base. (6) Award tent for cases requiring watching for twenty-four hours, or too bad for evacuation." Llewellyn was buried in Heilly Station Cemetery, close to the river Ancre. The following can be found at http://greatwarnurses.blogspot.co.uk/2007/02/heilly-station-ccs.html "Heilly Station, situated at Mericourt-l'Abbe, just north of the River Somme, and about 6 miles south-west of Albert. In July 1916, during the first days of the Battle of the Somme, the CCSs at Heilly were closest to the battlefield, but the last on the route taken by ambulance trains on their journey taking casualties back to hospital. They admitted thousands of men during those first few days, but the shortage of trains meant that no casualties could be evacuated for more than 72 hours. During that time, the death toll at Heilly was so great, that to save both time and space, men were often buried on top of each other, three to a grave. As there was so little room on each headstone for three names, the regimental badges of the soldiers had to be omitted, and instead the insignia of 117 separate units are incorporated into a cloister and screen wall at one end of the cemetery."

Because the gravestones did not have the space to carve the battalion insignia, a covered walkway was built and the insignia plaques are displayed there.

|

Home Programme Membership Archive War Memorials History Walk Miscellanea Links Contact Us